In sunshine or in shadow

Saying goodbye to my four-legged friend

Here’s the first of my 12 weekly posts (marked safe from financial ruin). This is a long one - something I’ve been drafting for a while - covering the hardest decision I’ve had to make in years.

This past Memorial Day, I headed home from a long weekend in Lake Placid with Ariana and two friends. We brought Voodoo, my 2-year-old pup, who tolerated the hours cooped up in the truck in return for a couple of long, slippery, happy hikes in the rain. After days of clouds, the sun finally shone. Spirits were high. We stopped for lunch at a dog-friendly place with a backdoor patio. I weighed my options, felt the heat in the air, and decided to bring Voodoo with us. It was a nearly fatal decision.

We sat at a table, Voodoo on leash, harnessed. He laid below us, quiet. A toddler wandered around, and I mentally exited the table’s conversation to track him with my eyes. He got a few feet behind Voodoo and stopped, staring. I could tell he wanted to pet, but I heard a low growl from below. My hands tight on Voodoo’s harness, I told his dad “he’s not great with kids,” and the boy was summarily scooped. Crisis averted, all was well.

But a few minutes later, I spied a newcomer couple out of the corner of my eye. They had a fuzzy white dog, a small thing, in tow. The waiter brought them towards their table, a few feet from us. I held Voodoo with both hands, felt him tense, saw his hair stand up. There was a moment of calm as they reached our table. Then Voodoo exploded.

He left my grip. He grabbed the other dog by the ear and head. Voodoo is sixty pounds of pure muscle. I dove onto under the table to separate them. The woman, the white dog’s owner, screamed and screamed. Her hands were in the mix. My hands were the mix, too, prying at Voodoo’s jaw. I thought surely this dog is dead, he’s killed this dog. I understood how seconds can feel like minutes. Finally, we got him off.

I laid back in the stones, both arms around Voodoo’s panting body. Red blood ran over the dog’s ears. The woman sat weeping, her hand dripping blood. There was a moment of shocked calm, the entire restaurant silent. Then the waiters asked me to take Voodoo away. I did. While Ariana handled the aftermath, I walked to a stone wall a block away and sat, and shook, and wept as Voodoo, a normal dog again, licked my face.

Ultimately, the white dog was okay. Some lacerations on the ear, an easy fix for their vet. The police came and filed a report, and an ambulance came for the woman. She needed stitches on her hand, which had gotten between Voodoo’s teeth and her dog. I don’t remember the drive home to New York at all, not one bit.

This wasn’t Voodoo’s first attack. It was simply the worst, the closest he got to killing something. I knew in my heart that we could not continue like this.

Voodoo came into my life late in the winter of 2023. He sat in the front window of Doggie Style Pets on Pine Street in Philly, impossible to ignore. He was, unequivocally, the cutest puppy I’d ever seen. I adopted him with my girlfriend, and it was a mistake, because we’d break up soon.

Yet we adopted him. It was a cold day when we brought him home, and he only made it a few blocks before he sat down, shivering. I lifted him and carried him back to our house, his head on my shoulder, wide eyes taking in this new city as it receded behind us.

Besides the usual stressors of puppyhood - house-training is no joke - Voodoo’s first months with us were full of joy. Our very first weekend with him, we drove him to Virginia, where I ran a race at Terrapin Mountain. He slept with us in the tent and greeted me at the finish line. We took him to Natural Bridge State Park, where we let him off leash and ran with him along the riverside. Those few moments, watching him run, all three of us feeling free, are some of my happiest.

At home, he was a source of constant entertainment. As I played Outer Wilds at night, he’d wrap himself around me at the top of the couch cushions, head on my shoulder. For months, he’d bound up our trinity house’s skinny steps, but was scared to go down, so I’d carry him from the third floor to the first. He played with other dogs. He sat and greeted every new person on the street.

But one day, later that summer, we were playing in the park when he attacked my neighbor’s dog over a fetch ball. It was sudden, violent, surprising. The other dog was okay, but we were all quite shaken. I thought it might be a fluke, but it happened with another dog, then another dog. A few months passed, and Katie and I broke up. I moved to New York, and introduced Voodoo to Prospect Park. The fights happened more often. We started keeping our distance from other dogs; what used to be carefree time in nature now felt pregnant with risk. Voodoo still had a few select dog friends, but they were few and far between.

I thought: this is tough but manageable. At least he’s good with people.

But then I brought him to my family reunion in the summer of 2024, and as we all laughed over a family picture, my 4-year-old niece - used to an agreeable Shiba at home - touched Voodoo’s nose, and he bit. She was okay, but this was new territory and shattered Voodoo’s definition as a people-friendly dog. I felt ashamed, stressed, and increasingly isolated with the burden of this reactive dog.

Over the fall and winter of 2024, Voodoo got steadily worse with humans. He bit Ariana, my parents, several sitters, and a half dozen friends. He even bit me - something I thought he’d never do - multiple times. I had to manage a growing list of niche don’ts around him: if he’s sleeping, don’t reach towards him with your palms facing down. Don’t get too close when he’s under the table. Don’t pet his lower belly, ever, even if he seems playful.

I started a spreadsheet of his biting incidents, which at peak racked up to several in a week. I remember multiple times when I had to tackle Voodoo in the park to separate him during a dogfight, would lay there holding him in the mud as he calmed down. I loved our walks, but I also came to dread them, how I could not let my guard down for a moment.

I hated our building’s elevator, full of wandering toddlers and tiny dogs. I found myself getting colder, meaner, walking away from kids who asked if they could pet him.

I thought: he must be ill, he must have something physically wrong with him. I got him a full-body exam and comprehensive blood test at the vet to make sure there wasn’t a health issue. There wasn’t; he was fully healthy.

One sitter told me “there’s something wrong in his head, and I can’t watch him again.” Another told me “I’ve sat 60 dogs and I’ve never felt so unsafe before.”

And each time, I would think “how much longer can I do this?” I would think “It was a mistake to get you.” And then some time would pass, and I would think, hoping against evidence, “You will grow out of this.” And then more time would pass and I would wonder if I would ever truly trust him around my own child. And if that answer was no, as it had to be, what road were we walking down?

But it’s hard to look into the abyss on a happy day, and plenty of days were happy: hours of fetch, lovely walks around Cobble Hill as the sun set. Play time with the toys from a new Bark Box. A discarded Van Leeuwen carton as a late-night treat. Magical thinking grew in these little moments of joy. But then he’d bite, a chill would descend, and the cycle would restart, an orbit of hope and dread and joy and terror.

Our Memorial Day experience pushed us out of this orbit into something beyond the pale. The sirens, the blood, the shock were windows into an unavoidable future. Voodoo would bite again, and again, and again, and every bit of evidence said it would get worse.

I needed experts. I hired Gabriel, a behaviorist in Brooklyn. He came over and we did a session with Voodoo. I hoped for some secret wisdom, the revelation of hidden decay at the root of things, fixable with some arcane canine commands. Gabriel worked some magic on Voodoo’s leash behavior, but he also confirmed my fears: even if you work on a dog’s reactivity around humans, using a muzzle to train them around new people, there is no guarantee that a dog who’s bitten will not bite again.

And so I began to listen to podcasts about behavioral euthanasia. Certified experts who had raised dozens of dogs talked through their stories. Point after point struck me:

Dogs euthanized for behavioral reasons were, 99% of the time, wonderful companions. It was the 1% that made the difference.

Dogs could grow up in the worst of environments and turn out friendly. Dogs could also grow up in loving environments and bite.

If you can’t trust a dog alone in a house with a 5-year-old, you can’t trust the dog, period.

We have institutions for humans who hurt others. We don’t have the same for dogs, which forces us into dramatic choices.

It doesn’t get better.

I’d been fighting the inevitable for a while. The afternoon I surrendered to it, I got on the G train, eyes dead. I went to Ariana’s as she was getting ready for a run. She skipped the run and I cried for a long, long time.

New York has a thriving at-home pet euthanasia industry. I contacted a vet named Dr. Ray and set a date, a few weeks hence. I felt a burden fall from me.

Voodoo’s last day would be June 23. It was hard to think of much else. We kept to our schedules - mornings in the park, evenings round the neighborhood. We made him pup cups galore.

Some days were light, easy, like we had nothing but time. He played, he rolled in the grass, he sat by our sides as we cooked. Those days were the hardest - if every day had been like this, all would be well. We’d watch over each other for another decade at least, until his fur grayed and his body slowed. And I wished that. I wanted that world.

Other days I could not get over how little time we had left. As he lay next to me in bed one night, I thought of how, according to the doctor, his cremated ashes would be used to help build reefs off the Jersey coast. I thought about how the breathing dog next to me would transform into dust, how the places where his ashes were destined to rest existed, under dark waves.

During his final week, I wrote this:

The moments go so quickly. I want to talk to him, I want to make him understand what’s coming, but he can’t understand. He has no concept of life and death. He has no expectation for how long he should be around. He likes being outside, he likes grass. He hates when I leave the apartment. Sometimes he wants our attention, sometimes he doesn’t want us to approach.

I’ll miss his breath on my arm as he lays high on the couch.

A few days before his death, I fell asleep reading in bed. I felt such utter peace, like I was carried and cared for. It’s hard to describe this sleep. It felt mystical, like I broke some universal law by waking up from it. I wanted to go back.

I hoped this was how Voodoo’s end would be. I hoped that he’d fade into a happy oblivion, dreaming of his favorite toys, the smell of grass, a downward-dog stretch on the carpet inviting me to play. I hoped my end would come like that someday.

I did what I could to make Voodoo’s last days good ones: park time and skirt steaks galore.

I’ll never forget “Cornbread and Butterbeans” by the Carolina Chocolate Drops playing through my ears as we approached Grand Army Plaza. Voodoo knew we were close, his ears back, a pep in his trot. The clawhammer banjo rang out in time with my step, Prospect Park splayed out before us. In that moment, life couldn’t be better.

But even on his last night, he lashed at me, bared his teeth at Ariana.

Which brings me to a question I sat with for a while: was he happy?

He enjoyed our company - like any dog, he loved to see us come home, hated to see us leave. But it was rare that he was totally at ease, like he was as a pup. There was an edge to him that sharped as he got older - a sensitivity, a distrust, a violence. Many dogs feel this way, especially in a city. But Voodoo’s unpredictability, his strength, his willingness to inflict damage were beyond my capacity for containment. He couldn’t go on. I couldn’t go on.

His last day came. It was Monday morning, and the city crawled outside. An oppressive humidity blanketed everything. Dr. Ray would come at 1.

There was odd normalcy to the morning. I made coffee and breakfast. I played Pet Sounds all the way through, my album of choice the last few weeks.

11 AM came, which meant it was time to give him his medicine. We had two hours left. I broke down then, the most intense sobbing of my life. I was on my knees next to him. He was concerned; licked my face, erasing the tears. He started drooling a bit, I think out of anxiety from the crying. Finally, around 11:10, I wrapped his pills in steak and cheese and tossed them to him.

Pet Sounds became Willie Nelson.

Then we sat and sat and sat. He put his head on our laps, sat his butt up against me. I got a text from the vet saying he’d be there in an hour. We went outside for the the last time. The heat bathed us. He didn’t want to walk far, so we came back. We had a few more normal moments as we waited.

Then Dr. Ray came. I muzzled Voodoo and put his leash on, then had Ariana hold him while I went into the hallway. I waited for the sound of the elevator. Finally, Dr. Ray appeared, rolling a black case, Voodoo’s casket. He said “I’m sorry to meet you under these circumstances.” We stood outside my door. I signed paperwork as he walked me through the procedure: two shots, the first to put him to sleep, the second to stop his heart. I would have to hold Voodoo and distract him with food while he snuck in and gave the shot. Across the door, inside the apartment, I heard Ariana hushing and comforting Voodoo. I went back inside. Voodoo was laying down with the muzzle on, Ariana with leash in hand. I told her the plan and got peanut butter onto the lick mat.

I held Voodoo across his chest, sitting next to him, looking towards the window. He wasn’t interested in the lick mat, but he stayed steady. Suddenly he lurched - the doctor had stuck the shot in his leg. Even I was taken aback, I hadn’t heard him come in. I looked behind me and saw him disappearing back into the hallway, a kindly angel of death.

I pulled off Voodoo’s muzzle as fast as I could. He wagged his tail and licked my face - nervously or happily, I couldn’t tell.

This set the timer for Voodoo’s last ten conscious minutes. He started to sway, became uneasy on his paws. He tried to get on the couch, and I encouraged it, thinking it would be a comfortable place for him to sleep. My last pictures of Voodoo are from these moments. He seemed genuinely confused. At that point, he was losing control of his back legs, and I had help him off the couch onto the carpeted floor. His face was going blank. He kept rocking his head back and forth, as if he were seeing things in his periphery. He laid down, and we helped him. I told him how much I loved him, again and again. I told him how good he was. I told him I was sorry. I saw Ariana’s tears dropping onto him from above. He kept sticking his tongue, licking his nose, slowing down, slowing down. His eyes faded but didn’t close. He stuck his tongue out and didn’t retract it.

At the ten minute mark, I wasn’t sure if he was truly out, because his eyes were still open. Ariana got the doctor. He came in and felt between Voodoo’s toes, a way to check if they’re awake. He assured me Voodoo was asleep. He told us to take our time, that he’d wait outside.

I don’t know how long this lasted, I don’t know what I said. I didn’t know how long to stay in that liminal space.

Eventually I asked Ariana to get the doctor, and she did. The doctor checked again that Voodoo was fully out, and said he would give the other shot to “fully slow things down.” The doctor shaved a rectangle of fur on his leg right over a vein, so easy to spot with his muscles. I watched the needle disappear into it.

I held his body, trying to feel for his final breath, but his breath had become shallow. Before I knew it, he was still. The doctor, sitting on his knees, listened with his stethoscope. “He’s passed,” he told me. I said “okay” and broke down.

I caressed his body, I kissed his head, I told him again that I loved him.

The doctor and I lifted Voodoo into the rolling casket, which was filled with blankets. It would have been a comfortable place to sleep. His head was towards me. I caressed his head again, kissed him one more time, and told him, one last time, that I loved him.

The doctor closed the casket. He was gone.

Loss takes a while to percolate through the body. For me, mourning started the day I decided to put Voodoo down, it climaxed at his death, and it echoed for weeks afterwards. I expected him by my side each morning, licking his chops for my yogurt bowl. I waited for his shifting sigh from his cage as I quietly worked in the apartment, but the cage was now gone.

For all the pain, though, my days became easier. The ambient stress that had plagued me for the past year dissolved. I could leave New York at the drop of a hat, and didn’t constantly check my phone for updates while away, expecting the worst. I could contemplate a future exempt from the elephant-in-the-room question of what I would do with this dog that bites.

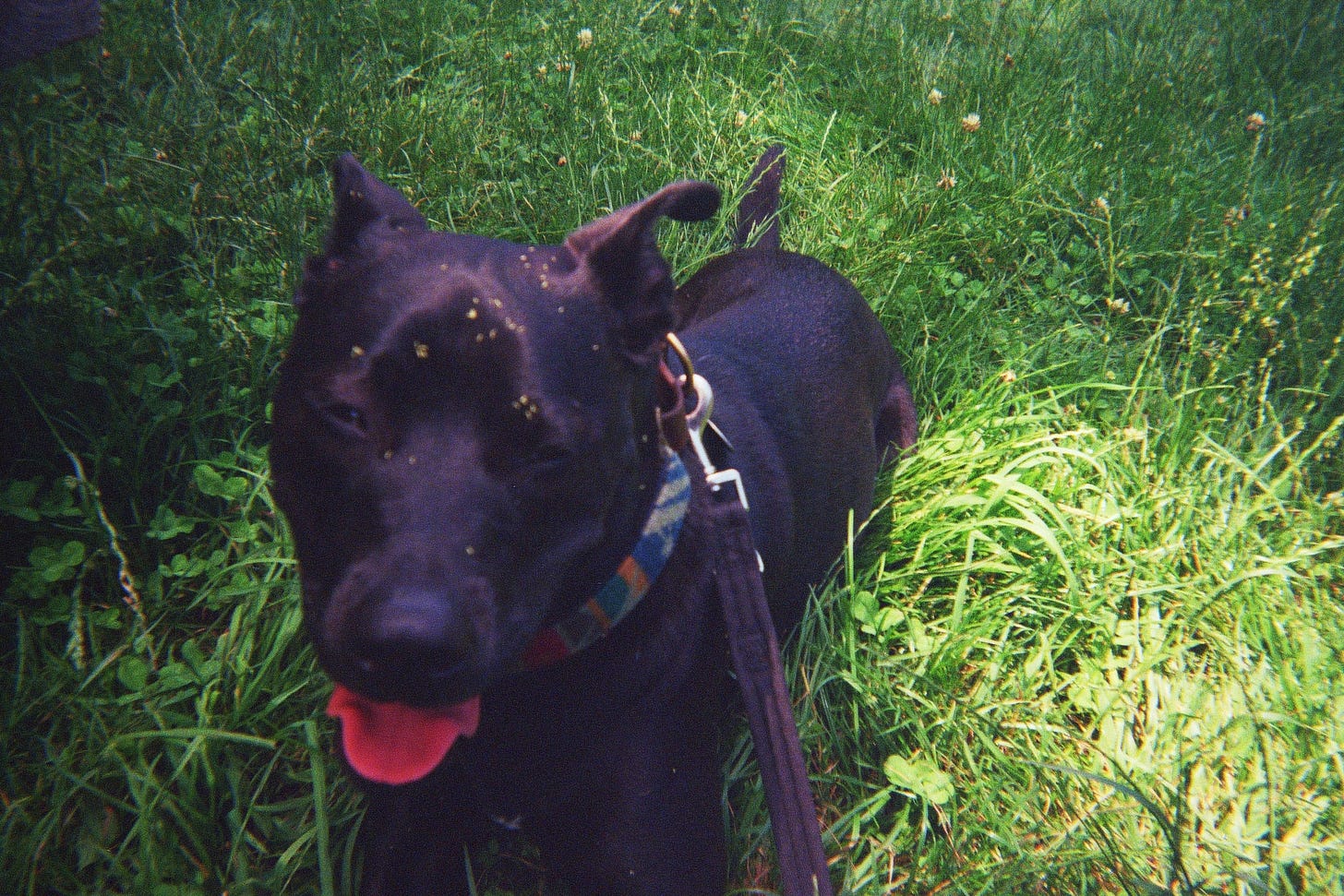

Life went on, plodding the same, chillingly neutral pace. I walked through our old haunts at Fort Greene. I got my disposable camera roll developed - the pictures throughout this essay. Half of them ended up too grainy to use, a loss I felt acutely. I met friendly dogs, like Tilly, our ranch dog in Colorado, who reminded me what it feels like to relax around a pup. I also met dogs that reminded me of Voodoo, like the six-month-old shepherd I met on Mt. Princeton who was already biting his owner; I saw the same encroaching worry in his owner, the same optimistic “He’s friendly but — ”.

And ultimately, I tried to glean meaning out of the experience, but the meaning was the experience. It meant something to adopt a creature, care for it, and navigate its wildness. It meant something to see how my parents stepped in when I most needed them, how my friends talked it out with me, how Ariana sat with me throughout it all. It meant, and still means something, to have had a relationship with this complicated animal.

So I’ll end this with the note I wrote the night before his death, when I was almost overwhelmed by his vividness.

I’ll miss his ears, their many expressions. I’ll miss his stretches. I’ll miss him laying with me on the couch. I’ll miss looking at his beautiful body shining in the sun. I’ll miss the way he frets over members of the group falling behind during a walk. I wish I got to take him on infinitely more hikes. I’ll miss him licking my face when I lay down on the floor. I’ll miss watching him run. I’ll miss the secondhand joy I feel when he’s sniffing something. I’ll miss the way he crosses his front paws when he lays. I’ll miss how he rests his head on your lap when he wants something, puppy-dog-eyes extraordinaire. I’ll miss how he digs himself under the covers. I’ll miss how he presses himself between you and the counter when you’re prepping food. I’ll miss how he humps me when I do yoga. I’ll miss his intelligence, his craftiness, even some of his willfulness. I’ll miss him.