Notes from China part 1

48 hours in

I’ve spent about 48 hours in Chengdu, China’s fourth largest city (21 million people, or LA + NYC). It’s in Szechuan province, home of China’s numbing-spicy cuisine (mala). It’s my first time in this country, a great feat after five visits to the Consulate General of the People’s Republic of China on West 42nd Street. There’s a whole lot to see, and I wanted to capture a quick assortment of my impressions. I’m editing this on my phone, so forgive any typos!

There are tons of electric cars, more than I’ve seen in any city. You can tell because electric cars have green plates and gas cars have blue. You can also tell because they sneak up on you silently.

China’s EVs are nice, they feel like Teslas. It was popular not that long ago to make fun of China’s EV industry, but it’s hard to joke about it anymore.

It’s surprising how car-centric Chengdu is. It feels like Houston with its massive highways and sprawling urbanism.

Didi, China’s uber, is usually cheaper than the subway - even for a single rider - and way more comfortable. Usually about $1-2 USD per 20 minutes.

Prepared food is abundant and cheap. I’m not sure I’d ever cook at home if I lived here.

Chengdu is cold and clammy right now - like 30 degrees F and 80% humidity - and it shocks me how everyone seems to just accept it. Windows rolled down in Didis, lobby doors wide open. Very rare to find a heated interior.

I have not seen cash once. Everything happens over Alipay or Wechat. My wallet feels redundant, and the single ATM I came across felt like a museum.

I’ve only been here for 2 days, yet this white boy has had many culinary firsts:

Mao tofu - tofu blocks covered with a fine hairy mold, cooked in oil.

Yellow tea, the rarest tea of the six types (green, red, white, yellow, dark, and Qing/oolong)

Also, I learned that China calls teas by their water color, whereas westerners call them by their leaf color. So what westerners call black tea, Chinese call red tea.

It’s also fun to dive into a more granular, specific tea culture. In the US, “green tea” is a monolith, but in China it’s a category that holds many, many subtypes with distinct flavor profiles. It’s like we’re saying “I like noodles,” while China is saying “I like fettuccine and bucatini and ravioli…”

We also steep our tea for way too long! Why are these packages telling us 3, 4, 5 minutes?

Frog legs, which taste more like seafood than chicken to me. Delicious, steeped in Szechuan peppercorns, fiery and numbing. I love.

Haw berries, sour and pitted.

Hotel breakfasts blow America’s out of the water. Steamed buns and xiao mai, made-to-order noodles and boiled dumplings. I didn’t miss the waffle machine.

“Beautiful women should behold beautiful things” - the woman running our tea ceremony at Heming Tea House.

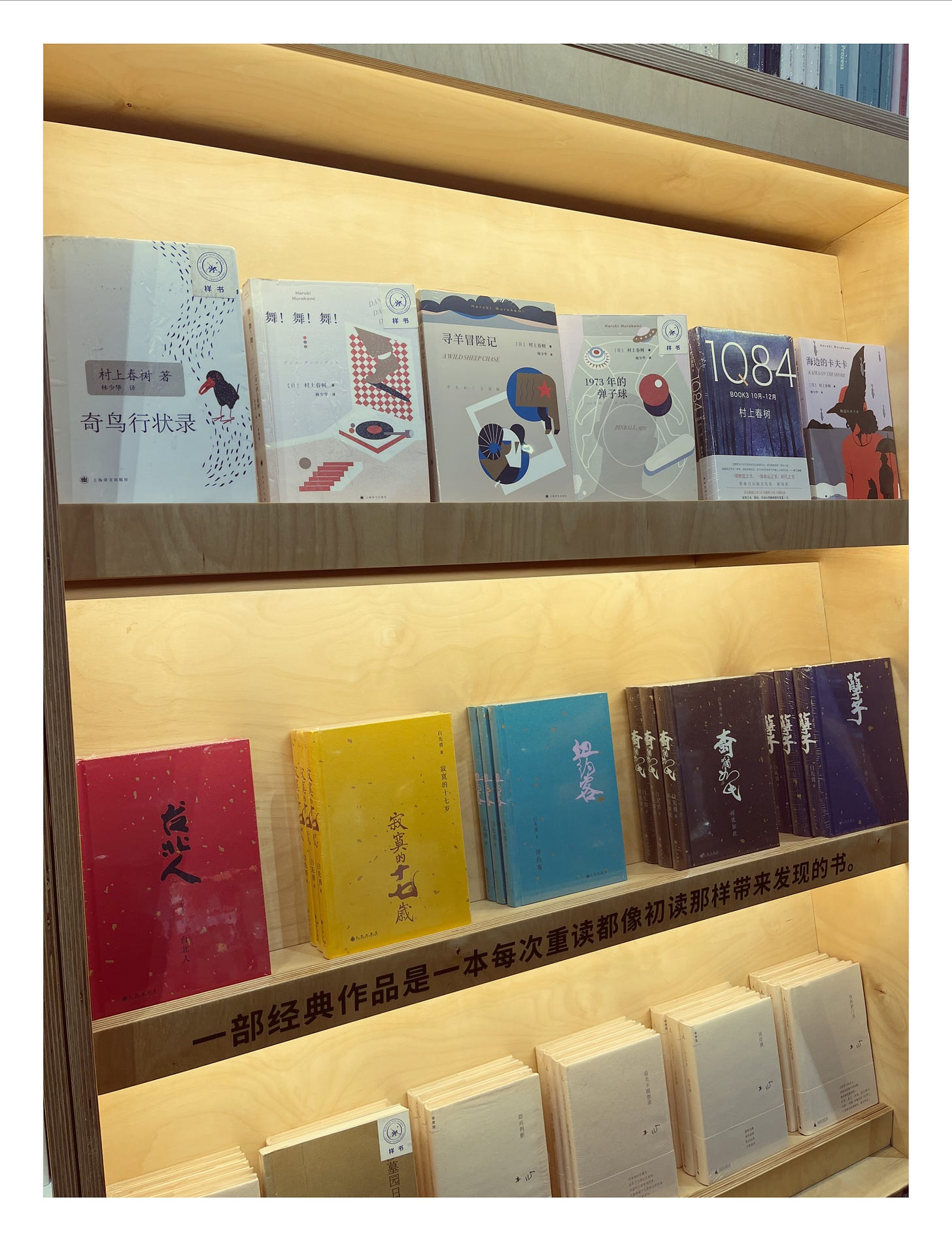

On beauty: books have such lovely covers here. It feels like every book cover in a western bookstore is yelling at me.

It’s trendy for young people to wear traditional Chinese dress, which I think is neat. It’s also common to dress up in full anime costumes, the likes of which you only see around Comic Con in the US.

I have no way to verify this but the only white people I’ve seen look Russian to me. Sometimes you can just tell.

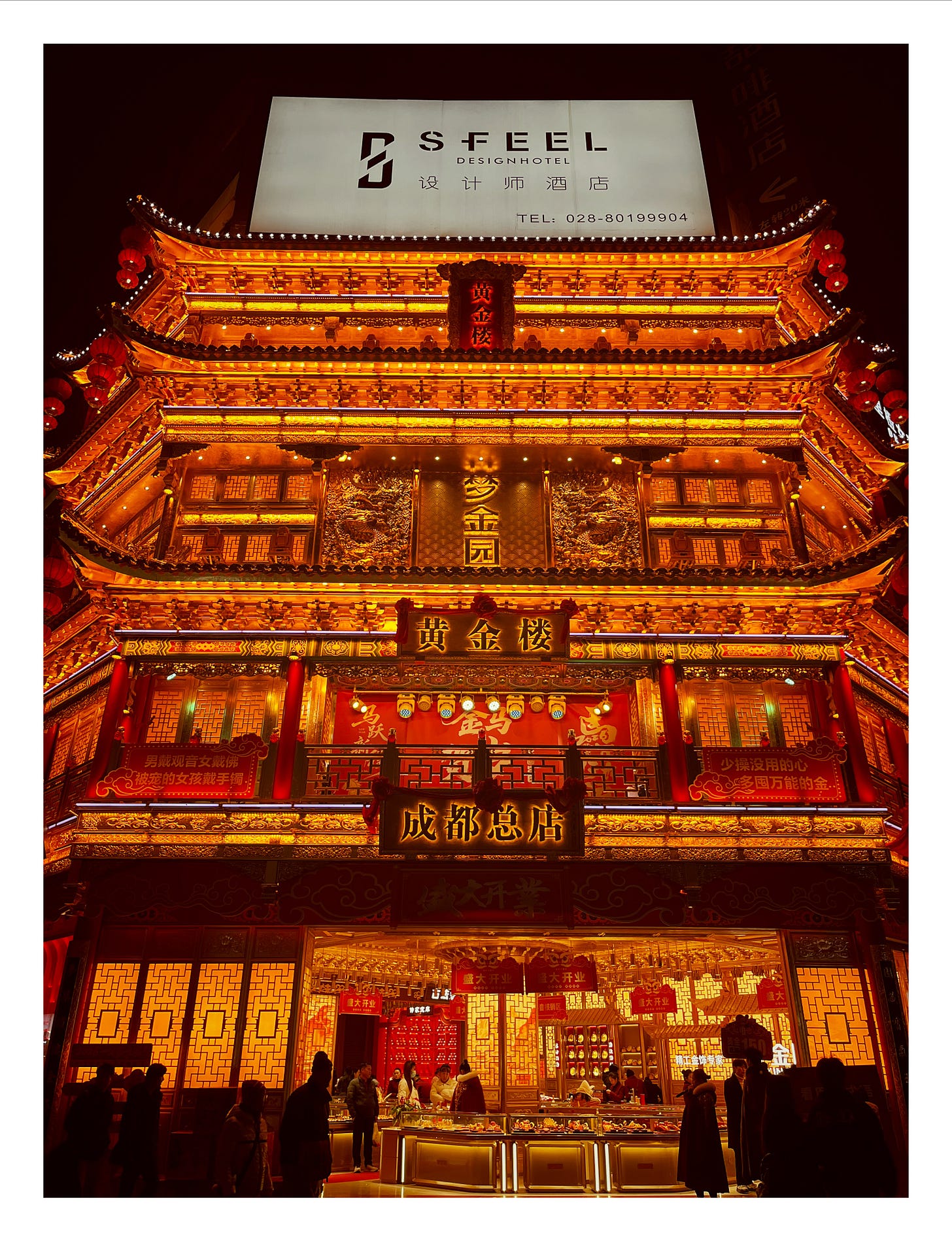

Chinese stores are serious about getting your attention in a way that you only find at the nicest department stores in the US. Opera performers with face-changing masks, dancing pandas, people in head-mics pushing you to try their samples.

On that note: why is in-person shopping so much less fun in the US? Why is mall culture ascendant in places in China and Indonesia but dead in the States? It can’t be because of Amazon; you can get stuff delivered to you faster in Jakarta and Chengdu. Is the cost of labor too high, thus no dancers? Do we have so many shows to watch that we’d rather order on Amazon from the comfort of our couch? Do we just not like strangers as much as we used to, given our politics? As a kid from the burbs, I’ve got fond memories of the mall, so this bums me out.

I’m lucky to travel with native Mandarin speakers. I think China - at least the less-touristy area of Chengdu - would pose challenges to non-speakers. English is not common, and the very limited Mandarin I trot out usually elicits surprise.

I’m sitting on a high-speed rail that’s tunneling for miles under 13-thousand-foot mountains, slowly climbing up to the Tibetan plateau. I simply can’t imagine a project like this in the US. We’ve maxed out our public works.

Call me a kool-aid drinker, but it’s refreshing to be in a country in which people seem proud of their heritage and optimistic about their future.