I’ve been finding joy in picture books lately. At a time when my brain yearns for the dopamine hits of infinite scroll, when I watch my hand reach for my phone with a mind of its own, there is something refreshing - even quietly revolutionary - about a detailed image painstakingly drawn unfurling across a page. No battery needed, just light from our sun and the eyes to see.

But not only have these books entertained me, they’ve surprised me. For all their beautiful illustrations, there’s so much unseen in these books, whole worlds a few feet down.

Here are three books I’ve loved exploring lately. One children’s book, one graphic novel, one manga.

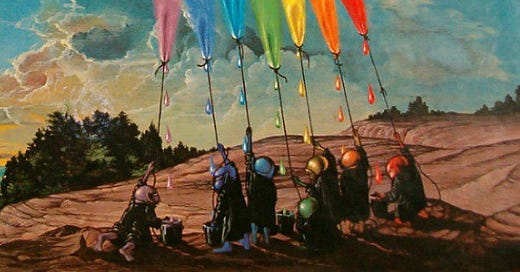

The Rainbow Goblins, by Ul de Rico

From the mind of Count Ulderico Gropplero di Troppenberg (or Ul de Rico, but where’s the fun in that) comes this eerie, beautiful tale explaining why rainbows never touch the ground. Every picture, from psychedelic dreamscape to sweeping natural vista, is framable and worth the price of admission.

Genesis allusions abound - the rainbow, the Garden of Eden, Noah’s Ark, even The Fall - but this world feels decidedly non-Christian. There is justice but no redemption; good triumphs, but it feels like a close one. It’s not clear whether things were definitely going to turn out the way they do, and because of that, this book leaves you feeling… wary? A bit afraid?

Oh, and if you want a groovy accompaniment as you read, Masayoshi Takanaka did a theme album.

Soft City, by Hariton Pushwagner

“Where is the mind when the body is here?”

We’re lucky to even know Soft City exists. Written by Hariton Pushwagner1 between 1969 and 1975, the entire work somehow disappeared until it was rediscovered in Oslo in 2002, republished in 2008. Now it’s earned the moniker “the lost graphic novel.” But wait, there’s more!

At its core, Soft City is a day-in-the-life portrait of a corporate dystopia. Like a lot of dystopias, it’s both alien and unsettlingly familiar. This particular dystopia is retro: Nazi references abound, the Controller is German, the nonsense-speak blasting newspaper headlines is a reshuffling of Mad Men-era ad campaigns (stuff like “soft bartender cream feeling” and “streamline first class business taste of life!”). But it’s also eerily futuristic: the entire city is controlled by Soft Inc. (decades before software would become a household term), the Controller surveils all from behind a screen, and the flashes of the world outside Soft City — student protests, starved babies, portents of nuclear war — might as well be videos from today’s Fox or NBC.2

What really makes this novel shine, though, are the hints at the human, the uncontrollable, even in the midst of its perfectly symmetrical plot (wake up, go to work, come home, go to sleep). Identical men drive identical cars to identical jobs, but one of them daydreams about being a fighter pilot while another imagines himself fishing. Hundreds of women with their hundreds of babies line up at apartment windows to greet the returning men, but one of them looks defeated, and wait, is that a man waiting in that window instead of a woman? The dutiful wife does everything right, but she counts to ten when kissing her husband and thinks “Crazy idiot!” to herself after serving him cream in his coffee. Tellingly, only the baby seems to get it: “How strange the world seems.”

You can read this as critiques of consumer capitalism, militant communism, or good old fascism, but the real rebellion here is against surrender to the soft, predictable, banal life that best aligns with whatever social structures exist. In Soft City, it’s unclear what happens to those who deviate from the path, though it’s hinted as the men line up for work with “If you don’t make it/You’re fired/If you’re fired/You are finished.” Nevertheless, seeds of thought-rebellion germinate.

But to what end? And what does it matter?

The Walking Man, by Jiro Taniguchi

If there’s a theme to these three books, it’s that something roils beneath. I have wondered about that lurking subterranean presence in The Walking Man ever since I finished it.

On the surface, The Walking Man follows a nameless middle-aged businessman as he wanders through suburban Japan. The illustrations are beautiful — black-and-white with splashes of sporadic color — and capture well the close coziness of Japanese urbanism. The walking man watches birds, stares at the snowfall. He adopts a retriever. These chapters are calming, the perfect antidote to the stressful day.

But the walking man also does weird things. He sneaks into a public pool at night, strips down, and does laps. He sprints up an apartment’s staircase in the middle of the night, only to pass out on the roof until the rising sun wakes him.

And the ending, the ending… I don’t want to give too much away, but suffice to say we go from chapters like “Tree Climbing” to “Tokyo Illusory Journey” and the vibe very much shifts.

What’s happening here? Are we descending into the walking man’s unconscious? Memories that may explain that yearning look in his eyes? Or are these just fantasies of a bored, imaginative middle-aged pencil pusher?

What a perfect name for the author of this book! The marriage of mechanical and living, scientific and artistic. Like Valve-beethoven or Pump-byron.

Which is really just to say that 2024 is so much closer to the early 70s than we might think.